Growing up in the Hampton area, the home of what is now called Atlanta Motor Speedway, we were exposed to car racing. We didn’t know much about the early days of NASCAR, which was closely tied to the business of moonshine. One of the first big NASCAR stars was Junior Johnson. Even after piling up victories, Junior would return home to help with the family business of moonshine.

Moonshine production got a big boost from two things that happened at roughly the same time, Prohibition and the Boll Weevil Depression. With the depressed yields from cotton, some farmers found they could make up lost income by making moonshine. If you couldn’t make it, you could make money transporting it. As Loretta Lynn once said about her husband, “Doo never actually made moonshine, but he hauled about an ocean of it.”

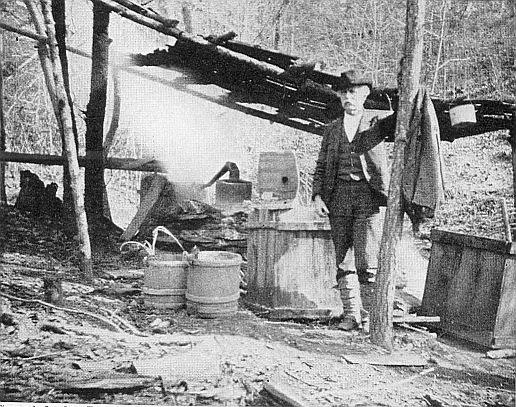

The process of making it was not complicated. Some water, ground corn, yeast, and maybe some sugar could make a decent mash. In as little as a few days up to a few weeks, the mash fermentation would complete. Sure, variations in the recipe made some difference, but the true skill was in the distillation.

As a chemistry major, organic chemistry was somewhat frustrating because it is one thing to get the reactions right, but something altogether different in separating the various products. Good moonshiners understood this.

Moonshiners produced four products from the distillation process. The first product they called the foreshots, which contain a lot of methanol (wood alcohol). This was discarded – if you let that get into the final mix, it could cause blindness or even death. The following product, called the heads, contained some of the lighter compounds that taste bad and smell like solvent. At this point in the process, the distillation was a third done, and none of it was fit to drink.

The third product was called the hearts, and this is where the money was. It was primarily ethanol, which boils at 172 degrees. It also had a slightly sweet taste, making it easier to distinguish between the heads. The final product was the tails, which contained heavier alcohols. The sweetness and smoothness of the hearts were also gone, and you may even get an oily sheen at the top of the distillate. Knowing what to throw out was part science and part art.

Even as I was growing up, they would occasionally find a still in the area. I always got mixed signals about moonshiners. Coming from a law enforcement family, I knew it was illegal. But, there didn’t seem to be much outrage against the people who made and distributed it. From the things I heard and movies like White Lightning and Gator, it wasn’t always clear who the bad guys were. There are stories about moonshiners in the area, and I’m not sure I believe most of them. One of them I’ll repeat here comes from my friend Gene Morris’ book*. In the 1940s, a still was busted in the area. The Sheriff allowed Gene’s granddaddy, Mr. G. B. Morris, to take the big steel mash tank home (he lived just down the road from us). He used it as a septic tank, and it was the only one they ever had, serving them well into the 1990s.

* True Southerners: A Pictorial History of Henry County, Georgia by Gene Morris, Jr.